Bush V Gore as an apportionment problem

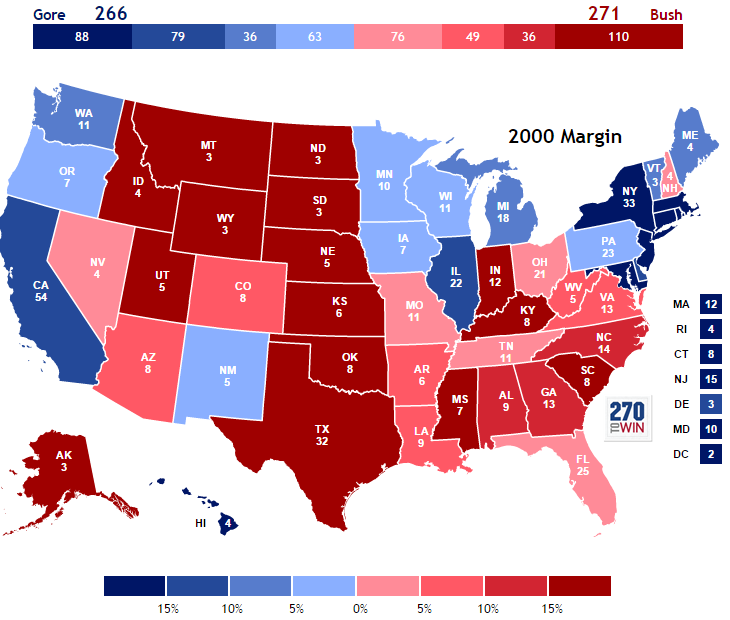

the 2000 election map Bush v. Gore.

1. US apportionment as a matter of algebra

In my previous post I discussed the Parliamentary apportionment in Thailand, and in the bibliography section I leave a remark that apportionment may be an important issue in US politics as well. Here in this post, I will give the readers a fun algebra problem around 2000 U.S. election, the most contentious one by far, Bush V. Gore.

The U.S. Constitution mentioned the term apportionment:

“Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed.”

The key word is “according to their respective numbers”. The Constitution left it to the House to decide how to calculation the apportionment. The issue is that exact proportionality is impossible due to the combination of two reasons: 1. the number of seats must be an integer; 2. the number of seats in the House are fixed. To accommodate these two reasons, a number of methods were devised.

We will consider 5 methods that were at one time used in US apportionment, the strength and weakness of each methods, and how each one can decide the 2000 US president. But now let us take a detour to look at the 2000 race.

Figure 1. The protagonists of our story. George Bush on your left, and Al Gore on the right.

2. Bush V Gore

I assume the readers know the electoral college; but many might not know how many of them there are and what is the connection to the House apportionment. Currently, we have 538 electoral colleges. The number of Electoral college of each state is the number of representatives plus the number of Senate; hence the connection to the House apportionment problem. Washington D.C. is a special case, whose electoral college is equal to that of the least populous state. So in total we have 435 house seats + 100 senators + 3 from D.C. making up 538 electoral colleges.

Bush narrowly won the razor-thin race in Florida and got 271 votes, while Gore got 267 votes (he actually got 266 votes after one E.C. casted a protest vote). Now there are so many issues one can talk about this election, ranging from the infamous hanging chads, the butterfly ballots of Palm Beach county, the supreme court decision to stop the recount. But let us consider in this very tight margin, can we reapportion the house seats such that the outcome be different? The answer is yes. In fact, we can arrange it so that we get a tie, and the last vote would be casted in the House of Representatives. So now that we know what at stake, let get back to what are the 5 methods.

Figure 2. The infamous hanging chads and dimple chads being frantically counted as the deadline approached.

3. Five methods of apportionment considered

The re-apportionment is generally done every decade, following a decennial census. US

3.1 The Jefferson method (invented by Thomas Jefferson) was the first method used from 1790 to 1832.

3.2 The Webster method (invented also by a famous stateman Daniel Webster) was used from 1840 to 1850.

3.3 The Hamilton method (proposed by Alexander Hamilton, also a stateman) was used from 1850 to 1900. This method although seemed to round the seats well, introduced a number of paradoxes and absurdity to apportionment, Finally, the Webster method was re-introduced in 1911 til 1940.

3.4 The Huntington-Hill method (by two mathematicians Edward Vermilye Huntington, Joseph Adna Hill) method was introduced in 1941, and is still the method used today.

3.5 The Dean method (by James Deam a professor of Astronomy at Dartmouth college). This method was never used.

4. What’s in each method

4.1 Let’s consider first the Jefferson’s method.

Jefferson Method

def Jefferson_method(df,House_seat = 435):

"""implement highest average method. This calculation is attributed to Thomas Jefferson who proposed this method in 1790s.

input

df = dataframe containing the state name, and the population number

House_seat = number of congressional seats total which is 435

output return dataframe contains number of electors apportioned to each state"""

df['congressional_seats'] = 0

while sum(df['congressional_seats']) < House_seat:

df['quotients'] = pd.to_numeric(df['population']/(df['congressional_seats'] + 1))

df['quotients'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 0 #DC does not have congressional seats.

df['congressional_seats'] = np.where(df.index == df.quotients.idxmax(axis=0), df['congressional_seats'] + 1, df['congressional_seats'])

df['JF_electors'] = df['congressional_seats'] + 2

df['JF_electors'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 3

return df

The idea behind this method is that for each seat awarded, we first calculate the quotient score, then the each congressional seat is awarded to a state with highest quotient score. The process is repeated until all seats are accounted for.

4.2 Webster method is similar to the Jefferson method, but the quotient is calculated slightly differently, so that the quotients of states already have large number of congressional seats are downweighted compared to smaller states.

Webster Method

def Webster_method(df,House_seat = 435):

"""implement highest average method. This calculation is attributed to Daniel Webster who proposed this method in 1832.

df = dataframe containing the state name, and the population number

House_seat = number of congressional seats total which is 435

output return dataframe contains number of electors apportioned to each state"""

df['congressional_seats'] = 0

while sum(df['congressional_seats']) < House_seat:

df['quotients'] = pd.to_numeric(df['population']/(2*df['congressional_seats'] + 1))

df['quotients'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 0 #DC does not have congressional seats.

df['congressional_seats'] = np.where(df.index == df.quotients.idxmax(axis=0), df['congressional_seats'] + 1, df['congressional_seats'])

#print(sum(df['congressional_seats']))

df['WB_electors'] = df['congressional_seats'] + 2

df['WB_electors'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 3

return df

The history of how this method replaced the Jefferson method is fascinating. read here for more information.

4.3 Then let’s consider Hamilton method as well.

Hamilton Method

def Hamilton_method(df,House_seat = 435):

"""implement larest remainder method. This calculation is attributed to Alexander Hamilton who proposed this method in 1790s.

df = dataframe containing the state name, and the population number

House_seat = number of congressional seats total which is 435

output return dataframe contains number of electors apportioned to each state"""

df['congressional_seats'] = 0

Hare_quota = sum(df['population'][df['State'] != 'DC'])/House_seat

df['quota'] = df['population']/Hare_quota

df['quota'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 0

df['whole_number'] = np.floor(df['quota'])

df['remainder'] = df['quota'] - df['whole_number']

df['congressional_seats'] = df['whole_number']

while sum(df['congressional_seats']) < House_seat:

df['congressional_seats'] = np.where(df['remainder'] == max(df['remainder']), df['congressional_seats'] + 1, df['congressional_seats'])

df['remainder'][df['remainder'] == max(df['remainder'])] = 0

#print(sum(df['congressional_seats']))

df['HA_electors'] = df['congressional_seats'] + 2

df['HA_electors'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 3

return df

Hamilton method operates from a different underlying algebra. Instead of awarding seat to highest quotient, seats are given according to quota. First, seats are given according to the whole number of quota each state receives. Then the remaining seats are given by rank of the remainder of the quota. This method has a big advantage of keeping seats for each state within the proportional quota, namely within +/- 1 seats from the exact floating quota number. However, it leads to a lot of “paradoxes”. read here for more information.

4.4 The Dean method was never used, but it is interesting. The idea is to calculate the quota, not from the arithmetic mean, but from harmonic mean. The property of the harmonic mean is that it mitigates the impact of large outliers and aggravates that of small outliers. In other words, this method favor the small states over the big states.

Dean Method

def Dean_method(df, House_seat = 435):

"""implement Dean method, invented by a professor of Astronomy at Dartmouth College

df = dataframe containing the state name, and the population number

House_seat = number of congressional seats total which is 435

output return dataframe contains number of electors apportioned to each state"""

D = sum(df['population'][df['State'] != 'DC'])/House_seat

df['congressional_seats'] = 0

def Dean_sub_function(df,House_seat,D):

df['quota'] = df['population']/D

df['quota'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 0

df['congressional_seats'] = np.floor(df['quota'])

#compare the quota to the harmonic mean

df['congressional_seats'] = np.where(df['quota'] >((df['congressional_seats']*(df['congressional_seats'] +1))/(df['congressional_seats']+0.5)),

df['congressional_seats']+1, df['congressional_seats'])

return df

gap = 1000

while sum(df['congressional_seats']) != House_seat:

gap = gap - 10

# we will keep adjusting the gap until the sum of apportioned seats to all state equals the number of seats

if sum(df['congressional_seats']) > House_seat:

D = D + gap

df = Dean_sub_function(df,House_seat,D)

elif sum(df['congressional_seats']) < House_seat:

D = D - gap

df = Dean_sub_function(df,House_seat,D)

df['DN_electors'] = df['congressional_seats'] + 2

df['DN_electors'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 3

return df

Notice that the divisor here has to be adjusted so that the quota it gives out to states sum to 435.

4.5 Lastly we consider Hungtinton-Hill method, which is the one in used today.

Hungtinton-Hill method

def Hill_method(df, House_seat = 435):

"""implement Hill method, invented by Joseph Hill who worked in the Census Bureau. This method is still used today.

df = dataframe containing the state name, and the population number

House_seat = number of congressional seats total which is 435

output return dataframe contains number of electors apportioned to each state"""

df['congressional_seats'] = 0

D = sum(df['population'][df['State'] != 'DC'])/House_seat

D = D

def Hill_sub_function(df,House_seat,D):

"""sub-function that takes 2 inputs from the main function and returns dataframe containing congressional seats

input D = approsimate number of population per seat"""

df['quota'] = df['population']/D

df['quota'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 0

df['congressional_seats'] = np.floor(df['quota'])

#compare the quota to the geometric mean

df['congressional_seats'] = np.where(df['quota'] >np.sqrt(df['congressional_seats']*(df['congressional_seats'] +1)),

df['congressional_seats']+1, df['congressional_seats'])

return df

while sum(df['congressional_seats']) != House_seat:

gap = np.random.randint(1,100)

# we will keep adjusting D until the sum of apportioned seats to all state equals the number of seats

if sum(df['congressional_seats']) > House_seat:

D = D + gap

df = Hill_sub_function(df,House_seat,D)

elif sum(df['congressional_seats']) < House_seat:

D = D - gap

df = Hill_sub_function(df,House_seat,D)

df['Hill_electors'] = df['congressional_seats'] + 2

df['Hill_electors'][df['State'] == 'DC'] = 3

return df

The idea behind the Hill method is that it uses geometric mean to calculate quota. We see all three types of Pythagorean means are used to calculate the proportional quota. The arithmetic mean favors large outliers while the harmonic mean favors small outliers. The geometric mean is always in between. Read this wiki article for the information and proof. So it fits with the spirit of compromise.

5 Result

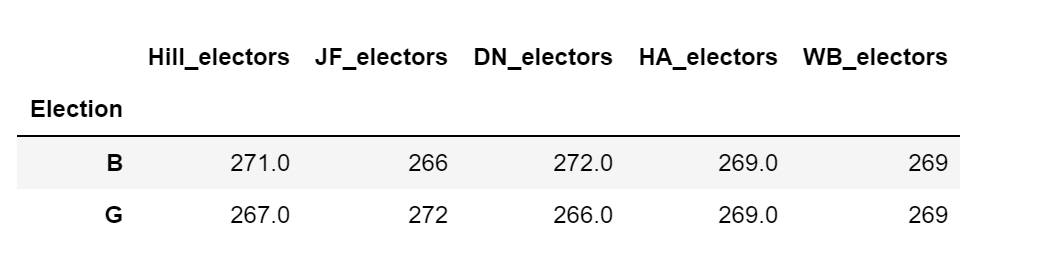

Here is what the 5 methods give us.

Figure 3. The electoral colleges Bush (B) or Gore (G) received from different method of apportionment. Noted that in case of tie, the election is decided in the House of Representatives but each state delegation has 1 vote.

If we consider the relationship among the three Pythagoren means, we see that the Hill method gives more seats to Gore than what the Dean method would have. Because the Dean method favors small outlier, this means that Bush is favored among smaller states.

In any case, it seems the Hill method will stay with us for another decade as the 2020 census is being carried out right now, and soon the there does not seem to be a big emerging debate in congress with the Hill method. The lesson of the story is to keep in mind that while we think of proportional representation as a concept easy to grasp, the reality of what is proportionality may be more difficult than you think.

read more: Pythagorean means

history of replacing Jefferson method with Webster method