Thailand Election's algebra problem

A passionate speaker's corner styled speech by Future forward party.

1. Suffrage as a matter of algebra

This blog is about my proposal to criticize the election law and electoral allocation procedure. I also want to put forward a way to make the the procedure clearer and easy to understand. In my previous post I laid out an argument why the current electoral system is terrible in that it favors small parties, and that in long run tends to fracture political coalitions. Here is another post telling why the Election law is terrible. The election was held by March 24 2019, and as of now, March 31, 2019, the election commission has not released the party list result. Actually there has been a great deal of confusion over how the election law determine the party lists. Most intellectuals, lawyers, and afficianados who have interpreted the law come up with either one of the two methods of calculating party lists. The actual election law is quite difficult to understand, the laws are intercalated, and have a lot of nested conditional clauses. The law make references to other parts of the law; and the lack of mathematical notations makes it difficult to follow. You can read how the calculation is done here in this blog by professor Allen Hicken.

This kind of confusion highlights gross incompetence of the election comission. Moreover, it casts doubt on the legislative process done by the national legislative assembly.

2. The problem with the calculations

Now, I have my thought on which one is correct, since my previous blog implements that method. Simply put I think the 2nd scenario makes more sense from the mathematics point of view. The first scenario takes too many seats away from too many people who vote for a big party and gives them to small parties.

The first method distort the voting power of people because of the scaling problem. After calculating the first round of eligible party list seats, it scale the number down to 150 (the number of party list seat). Geometrically, the scaling is akin to shrinking the floating number line from 0-infinity to 0-150. The farther out you along the number line, the more shrinking you will see. In our case, it shrinks the number of a party having more eligible party list seats disproportionally more than a small party that doesn’t yet have party list.

The 2nd scenario keeps the shrinkage low because it shrinks the integer number line from 1-infinity to 0-150. As a a result, the allocation of a representative of a giver party to the voters is close to the ideal voter per represenative (about 70000 voters per representative).

If one thinks about the purpose of the election procedure, I will argue the main purpose the election must satisfy is to allocate representation fairly. Furthermore, one criterion for fairness is proportionality. A number of votes per representative should be roughly equal for all parties. That is to prevent a vote given to one party to have more power than another. The 1st scenario violates this criterion. A voter per representative for a small party is approximately 30000; while a voter per representative for a larger party can be up to 78000. A vote given to a large party worth half as much as a vote given to a small party. In 2nd scenario, the voter per representative is about 71000 across all parties. So I argue that while the 1st scenario violates the purpose of the election, the 2nd scenario satisfies it.

3. the edge case

After the scaling, there can be more than one party who gets assigned the same number of party list down the last decimal point. This is because the number of party list before scaling is an integer (not a floating number). If two party has the same party list seats before scaling, it will have the same number of party list seat after. And that create a potential problem. That is, what to do in case of a tie. Imagine a case that there is one seat left to allocate but two or more party are assigned the same number party list. The problem is the law does not say.

4. A proposed solution

So I come up with a proposal to do away with the confusing method, to cover the edge cases (in case of tie), and avoid re-scaling (which can distort a voting power). I wrote up a procedure as a python function that takes in pandas dataframe and return dataframe with the calculated representative seats. The method of allocating seat is inspired by Jefferson method (after Thomas Jefferson). The code is shown here.

def Jefferson_method(df_copy,max_seat = 500):

"""implement highest average method. This calculation is inspried by the Jefferson method (attributed to Thomas Jefferson).

The change is we remove votes that is attributed to district seats out first, and calculate the voters unaccounted for by district seats,

by allocating party lists to the party."""

df = df_copy.copy(deep=True)

df['party_list'] = 0

voter_per_rep = (df['voters'].sum()/max_seat)

df['unaccounted_for_voters'] = np.where((df['voters'] - df['district_won']*voter_per_rep) > 0, df['voters'] - df['district_won']*voter_per_rep,0)

while df['district_won'].sum() + df['party_list'].sum() < max_seat:

df['quotients'] = pd.to_numeric(df['unaccounted_for_voters']/(df['party_list'] + 1))

df['quotients'][df['Party'] == 'etc'] = 0 #these are pool of too small parties (a few hundred votes that will not be counted. so the quotient is set as 0)

df['party_list'] = np.where(df.index == df.quotients.idxmax(axis=0), df['party_list'] + 1, df['party_list'])

df['total_seats'] = df['district_won'] + df['party_list']

return dfRoughly, we calculate the voter per representative first. And use that number to find out for a given party, how many voters are left unaccounted for by the district representatives. These come from voters whose party lost in districts. Their voice is rescued by the party list so to speak. Then from the unaccounted-for-voters, we calculate a quotient by dividing the un-accounted-for-voters by number of party list plus 1 (to prevent dividing by 0) quotient = unaccounted-for-voters/(party_list + 1). Then a single party list seat is awarded to the party with the high quotient successively until the the total seat of representatives is 500 (this is represented by the while loop).

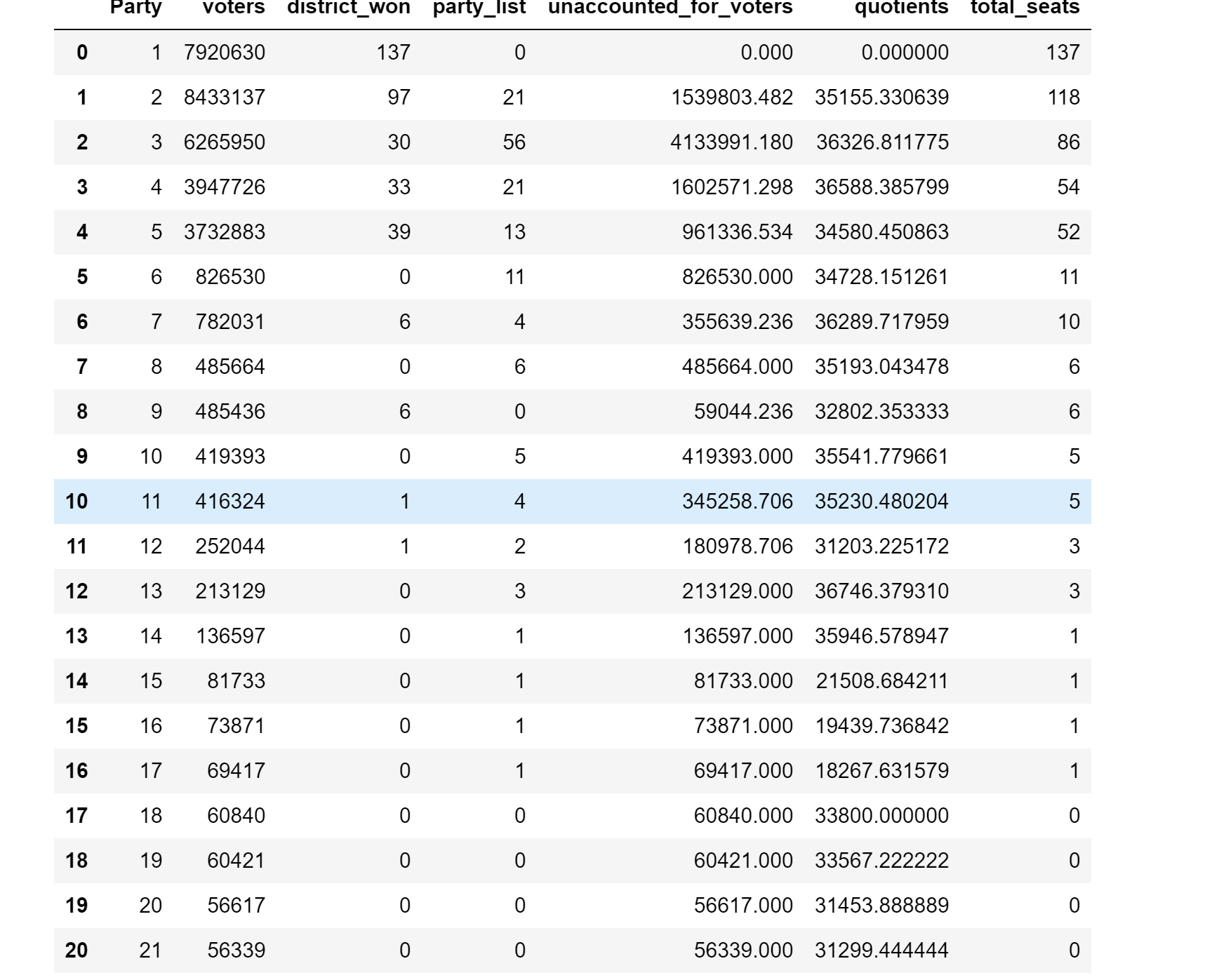

The election result calculated by this procedure is shown here.

Figure 1. The representative seats of Thailand election of 2019 calculated using my proposed method.

This method solves following problems: 1. the allocation is more proportional than the 1st scenario and always almost identical to the 2nd scenario, 2. easy to understand and implement than the 2nd scenario, 3. there is no scaling problem, so we avoid distorting the proportionality, and lastly 4. there is no tie since we always add one single seat at a time, and it is implausible for two party to have the same quotient (to have the same quotient they must have the same number of voters). Thus, we cover an edge case. In the end, I hope that my post here shows how writing a good law might be benefited from having a clean code in mind. I hope that the lawmakers of Thailand may learn something from the coders.

Read more:

- Jefferson method the procedure I proposed is inspired by the “Jefferson method”.

- Hamilton method the method currently used in Thailand is inspired by the “Hamilton method”.

- Balinski-Young theorem this is a nice article talking about a common sense violation that can arises from electoral procedure. Specifically, Balinski-Young theorem shows that the Hamilton method satisfies quota rule, but creates Alabama paradox and population paradox; while Jefferson method is free from Alabama paradox or population paradox but may not satisfy quota rule.

- apportionment problem in US presidential election A nice blog explaining how rounding of apportionment (or lack thereof) created the first US president who lost the popular vote. We are talking about 1876 Hayes V. Tilden. Also in the most controversial Bush V. Gore election of 2000, Al Gore would have won (271 electoral votes) under the apportionment by Jefferson method. The result would have been a tie (269 for both) under the Hamilton method. So now we know, suffrage is a matter of algebra.