Thailand Election 2019

Thailand, my motherland, will hold an election in March 24th, 2019. The purpose of this blogpost is to predict what outcome can we expect from the recent change in electoral system i.e. how members of Paliaments (MPs) are allocated.

First we will start off with some historical background (which you can skip if already known to you), then we will learn about two main electoral systems that are relevant to our discussion, and then we will apply them to the context of Thailand. We will take the outcome of 2014 election and apply it to 2019 election.

1. Historical background

Thailand has been through rough and tough time politically since the military coup of 2006. The country has since changed 6 prime ministers 4 constitutions. Due to international pressure as well as domestic discontent, the military regime is forced to hold a Democratic election in March 2019. However, no one fails to notice that the recent changes in the constitution is brought about by the military dictatorship regime to curtail the power of the major populist party. Among many changes, one that trigger my attention is the method of members of Parliament allocation.

Figure 1. Protestors campaigned for election (initially to be held on 24 February 2019, but was postposed to March).

2. Electoral System

We will consider two methods that are used in recent Thai election; as well as the methods of rounding. First is called two-tier (proportional) party list which was implemented in the Thailand constitution of 1997, and the second is called mixed membered apportionment which is implemented in Thailand constitution of 2016, and will be used in this up-coming election.

two-tier party list

Most readers may not be familiar with the party list representation. Essentially, members of Parlianment (MPs) are grouped into two: voting-district winners and elected party-list members. Let’s say a country is divided into 400 voting districts, we will have 400 MPs. Additional 100 parliamentarian seats, called party list, are given to a party based on the number of nation-wide popular votes. One way to allocate party list is to make it proportional to the whole nation-wide popular votes. In our example, suppost 300 districts are won by party A, and 100 districts are won by party B. A gets additional 75 seats as party lists, and B gets 25 seats.

mixed member apportionment

Similar to the two-tier party list system, constituents choose district representatives. Nation-wide votes are counted to determine how many total representatives each party will be allocated; let’s call this number the apportioning seats. The additional party list MPs will be added (if at all) to the district representatives to make the total MPs of a given party equals the apportioning seats. This creates a funny situation when a party wins more districts than the apportioning seats are given to them. The district winners above the apportioning seats are called overhang seats. That party will not get any more party-list seats. Imagine, party A wins all districts by a very small margin for each district, A will gets all all district representatives, but it’s unlikely that A will get a party list.

This way of allocating seats give a small party (often single-issued party) a chance to be represented, because even if it doesn’t win any district, it might be awarded party list. However, it punishes a big party, by not awarding any additional seats in case of overhang.

The overhang seats will be important later on when we see the situation in Thailand.

Method of rounding

Often when a party list is allocated to parties, the exact proportionality is not possible one has to round the proportional seats often a fractional number to a whole number. The question is to round up or round down, and how to keep the total seats after rounding under the desired number. There are numbers of methods, but the method used in Thailand election is called Hamilton method or largest remainder method.

Hamilton method

This method is named after Alexander Hamilton, who invented it in 1792. It allocates the party list seats according to “quotas” each party has. A quota represents a rough number of votes required for a single seat. For example, if there are 1 million votes and 100 seats to be allocated, a simple quota (also known as Hare quota) is 1 million/100 = 10000. That is, roughly a party will be awarded 1 seat per every 10000 votes it has.

Now the problem arises when there are parties with fractional quotas; so we need rounding of some kind. The rounding rule is as followed. First apply a floor function, that is, takes integer of quotas and award parties accordingly. Then if there is any remaining party list seat to be given, a priority is ranked by the fractional remainder (i.e. the decimal points), the largest remainder is first in rank. One additional seat is given to a party according to the remainder ranking.

3. 2014 Election Result

Thailand has a lot of political parties (53 parties run in 2014). We have, however, 2 main parties: Puer Thai (PT) party, a more economically liberal, rural-based, showing populism tendency (sort of like Bernie Sanders); and Democratic party, more economically conservative, urban-oriented, and has tie to elite establishment (sort of like Bush-Romney type).

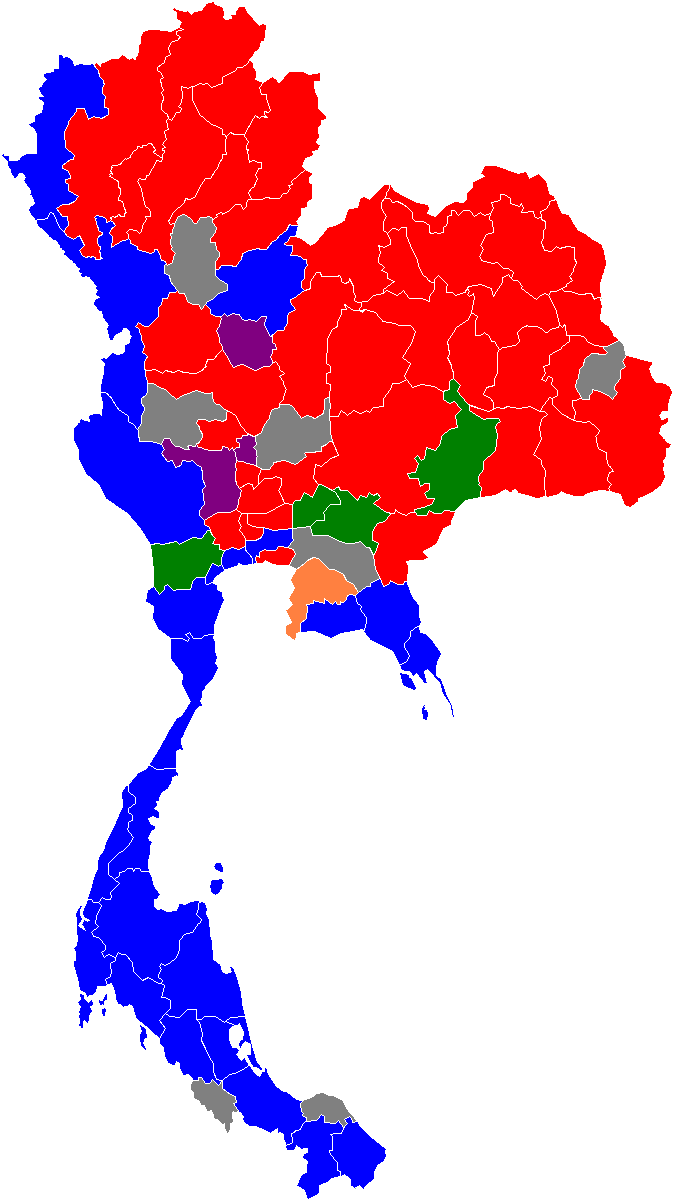

Below is the 2014 election map. Notice the regionalism. The red represents provinces won by Puer Thai, and the blue represents provinces won by Democratic party.

Figure 2. 2011 election district winner result. the red represents the provinces won by PT party, the blue represents the provinces won by the Democratic party.

3.1 Proportional party list representation

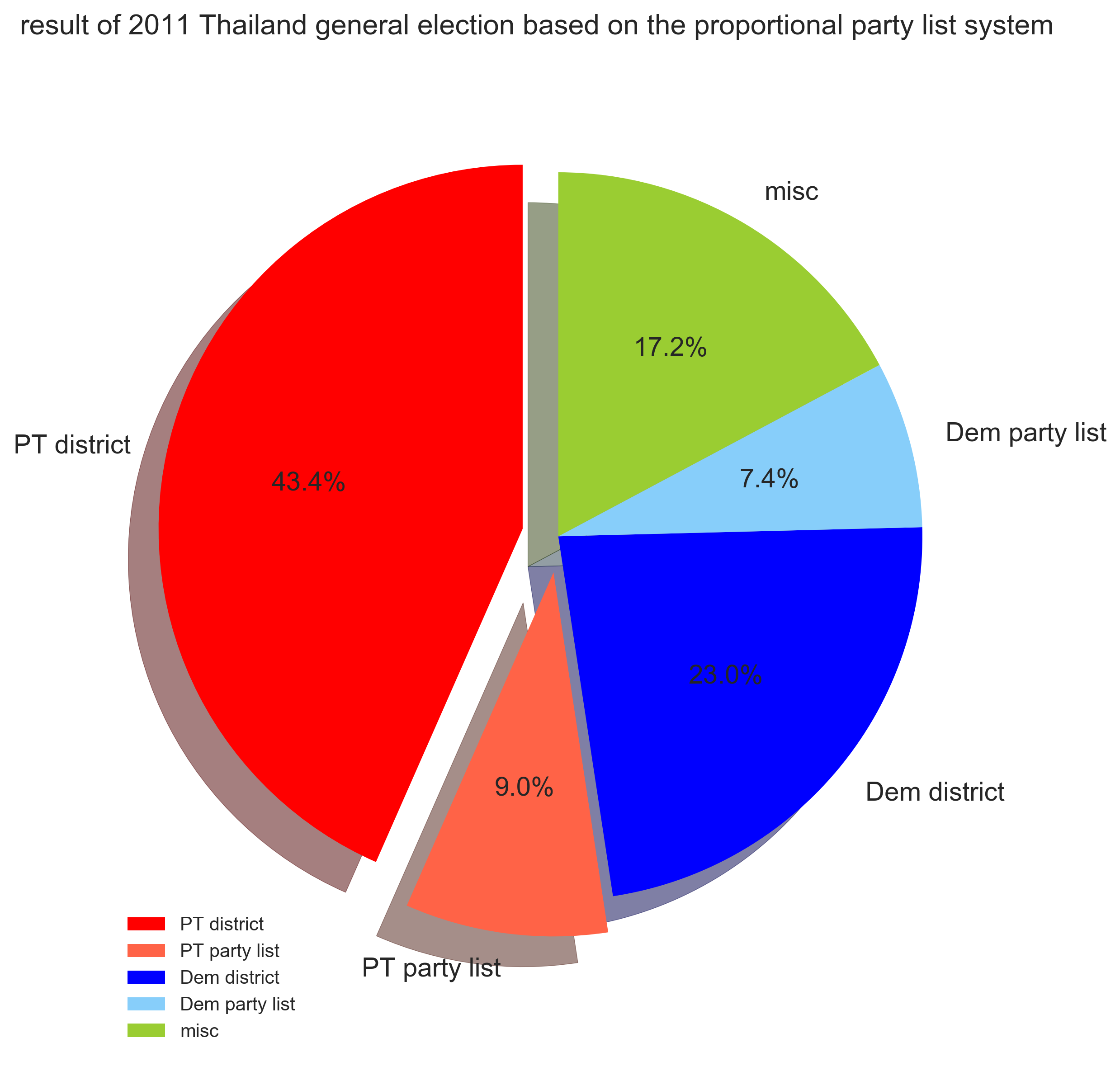

What you see in figure 2 is the district winners. Recall that the party is awarded party list seats proportional to nation-wide country votes. The total seat is shown here.

Figure 3. 2011 election result. the district winner and party list is shown separately.

4. 2019 Election prediction

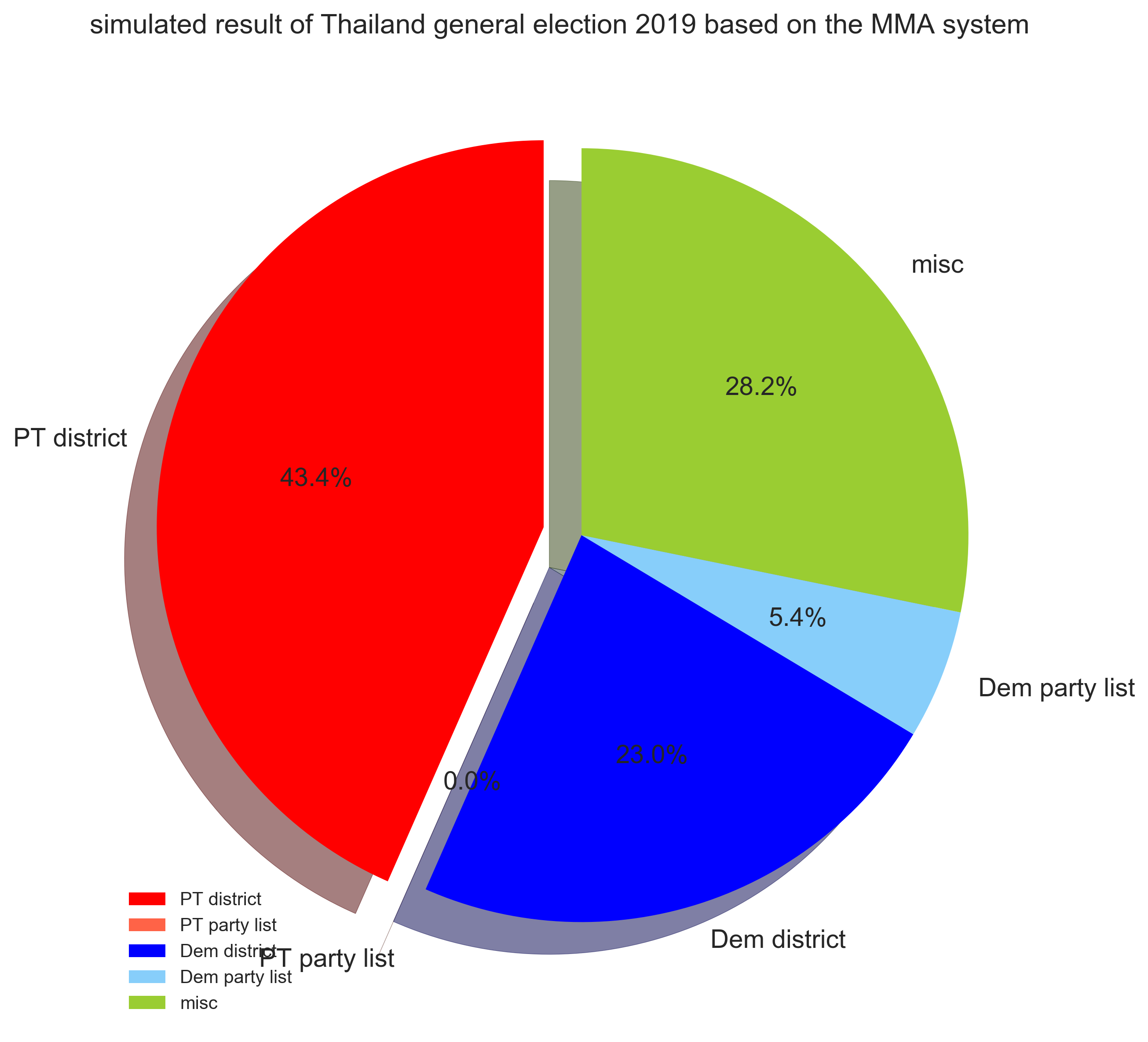

One good way to illustrate what the change in electoral system will cause is to just assume that the voting preferences of people do not change much, and the district lines are exactly preserved, and the only change in just the system. Here we will take the voting data of 2014 and project it to 2019. We then will calculate the party list using 2019 system. The result is shown below.

Figure 4. 2019 election prediction (based on 2011 voting preferences). the district winner and party list is shown separately.

Notice that PT does not get any party list at all. This is due to the problem with the overhang seats. We can say that MMA system penalizes them (which is obvious because the military regime wants to curtail the populist chance to get into office). Previously PT can form a stable government with the MPs they got, but according to the MMA system, it would be much tougher for them to do that. They will need to form a governmental coalition.

Analysis

Fortunately (or unfortunately as we shall explore further) there is a counter measure to the MMA penalty. Let start from what we know. We know that the MMA system penalizes the big party. This is because the nation-wide votes of the party are accounted for by both the district representatives and the party lists. If the party wins a slight majority in many districts, these district seats are overhangs. As a result, the party risks not gaining as many party lists as they would in other systems.

5. Counter-measure

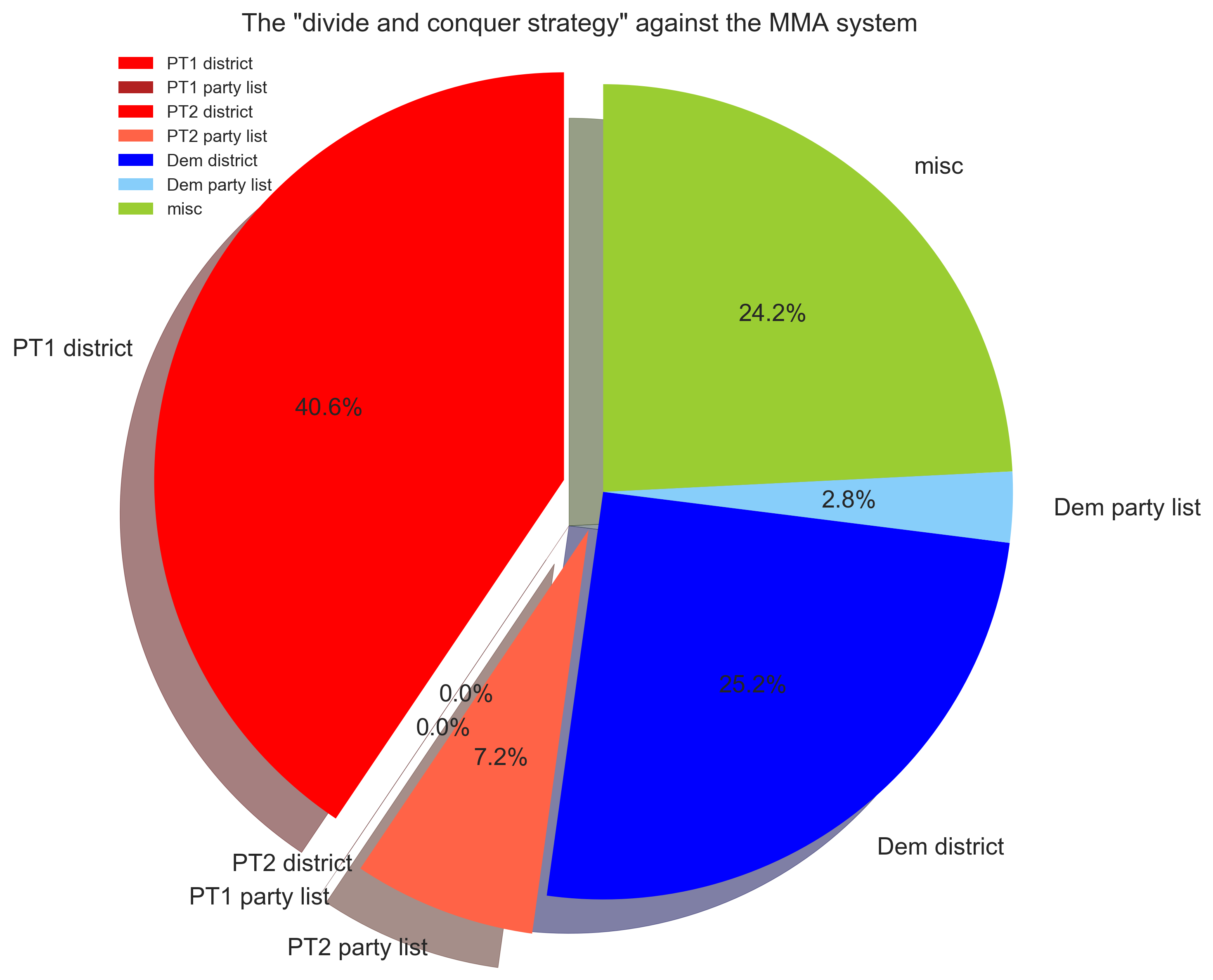

Just imagine if we can create a branch party (a nominee so to speak) to help the main party collect more seats. You ask “how can this be? That sounds like getting more votes out of nothing.” Let me show you how. We will simulate the election assuming that the voting and all the districts does not change in the population. All that is change is that we have a branch party that strategically runs in certain districts and not run in other districts to maximize the seats. I call this “divide and conquer strategy”. Below is the chart showing the result.

Figure 5. 2019 election prediction. branch party runs strategically to maximize MP seats

The result shows that by simply running a branch party, the combined effort can bring back the lost seats to almost the 2014 status quo level. It almost recovers to 2014 level. The secret is to think which districts to run the branch party.

6. The secret of coordination

I group the districts into 3 groups: trailing, toss-up, and leading (or likely).

In the “trailing” district, where the chance of winning in that district is near zero, the main party should not run there, but should run the branch party instead. By running the branch party in those districts, the branch party may get nation-wide votes enough to receive a party list, without getting any district win. The key is that the main party should avoid trying to get party list, because the overhang seats they have will prevent them from getting any party list.

In the “likely” district, where the main party is guaranteed to win by big margin, the branch party should also run in those districts to skim the votes beyond the margin to win. Any additional votes beyond the margin is really not needed to win in that district.Therefore, the branch party can take those votes to account for the party list. This strategy requires almost perfect coordination, because if the branch party performs too well, and take too many votes away from the main party, the main party might lose in that district.

In “toss-up” districts, it may be better to not run the branch party along side the main party because, while the chance to get enough votes from this district to gain paty list seat is unlikely, the party has greater risk to lose in this “toss-up” district if it split the votes in two.

Conclusion

We can speculate about the impact of this Constitutional change in electoral system on what Thai politics will be like. From our analysis above, for a big party to gain advantage, it must split up. This fracturing will create a big problem later because it is more difficult to unify smaller parties to form a stable government. It is akin to negotiating multilateral agreement. It is easy for a small party to demand a lot from the big party just so that the coalition has enough vote to pass a law. So the eventual effect would be that it is more difficult to form a stable coalition, and Thailand will, therefore, has a weak, unstable government. The rocky road is ahead for Thai people!