Bayesian Approach for Measuring Ads Conversion Lift test

The tsunami of online ads we all face everyday.

What is Lift test?

A familiar scenario seen in most companies with on-line presence is how to assess the efficacy of online ads. There are many ways to measure the efficacy, but the tried-and-tested method is to perform an online lift experiment. Facebook has a good description here of what an experiment looks like. Roughly, the audience are randomly assigned into two groups: control group or test group. The test group has an opportunity to see an online ad; and the control group does not. The opportunity to see an ad does not necessarily mean that the ads are shown to them. It merely indicates that they can see the ads.

The goal of this experiment is to find lift which is the success that is attributed to the audiences seeing an ad.

At the end of the experiment, we observe a number of audiences in the test group convert to become customers (buy the product) (c_test). A number of audiences in the control group also convert (c_control), perhaps at a different rate. The conversion in the control group is the baseline conversion rate. A reach happens when an ad is successfully shown to the test group. A number of audiences in the test group that is reached by an ad and also convert (c_reach). The dependency of the reach on the test group creates a heirarchical structure in the model that will be explored further when we talk about the modelling.

Now, you must realize that among these reached audiences who convert, some of them would have converted had the ads not been shown to them. This is due to the baseline conversion. The task here is to find, after accounting for the baseline conversion, how many reached audiences convert above and beyond the baseline level. That is the lift. The way we can think of the lift conversion is in term of a proportional impact in our model describing how many people will convert given they see an ad compared to not seeing the ad. This is a simplistic description of course. For more discussion (i.e. what if the ads were run to general population before the experiment, will it affects our interpretation of the experiment?) see the appendix.

So to illustrate I will show a simple experimental result below

# the data that we will need. I make these number up, so if the lift looks too high, you know it ain't realistic.

n_control = 4e+06 # number of people in control group

n_test = 4e+07 # number of people in the test group

c_control = 1400 #number of people in the control group who convert

c_test = 18000 # number of people in the test group who convert

c_reach = 6000 # number of people in the test group who see the ads and convertThe Bayesian approach

As I said earlier, the model is hierarchical in the sense that the probability that a reached person will convert is contingent on the probability of him/her being reach, which in turn also contingent on him/her being in the test group. The estimate of the proportional impact, as well as its uncertainty, has to capture this hierarchical dependency. One way to do it is to perform Bayesian hierarchical modeling. In Python, this task is implemented in Pymc3 package.

Esentially, Pymc3 implements Markov chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. For more information on the MCMC, read the appendix.

The estimate gives us a distribution of plausible values of the lift. The distribution reflects the uncertainty we have about the lift result, i.e. the degree of belief that the true lift impact may falls within the range.

Python packages needed

import numpy as np

#from numpy.random import beta, binomial

#import math

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('classic')

%matplotlib inline

import pymc3 as pm

import theano

from theano import shared

import theano.tensor as tt

print('running on theano ' + str(theano.version.version))

print('Running on PyMC3 v{}'.format(pm.__version__))

import warnings

warnings.simplefilter(action='ignore', category=FutureWarning)

Calculation of the Lift

First of all, since the number of participants in the control group and the test group are not equal, we need to re-scale so that the subsequent calculation are comparable.

scaling_factor$ = n_test/n_control

Secondly, we know that c_test > c_reach, which means that there are numbers of people who subscribe even when they do not see an ad. This is a baseline conversion. We need to calculate baseline in the test group

baseline =c_test - c_reach

we do not know the number of baseline in control group but we can assume that the baseline_proportion is the same; therefore,

Y = n_control x scaling_factor - baseline ; Y is the number of conversion in the control group who has an opportunity to see an ad but did not see it.

Lastly, we need to calculate Percent Lift which is percent of success attributed to an ad reached.

Lift = (c_reach - Y)/Y

Probabilistic programming with Pymc3

what does the model look like? We assume that there is a probability p for each person converting in each group (we have 3 groups: the control, the test, and the reach; the reach is a subgroup of the test). The observation we have for the model is m person converting out of a group of n audiences. Then the posterior is a binomial distribution of m successes from sample size n with the probability of success = p.

The conjugate prior of binomial distribution posterior is a beta distribution. So we need the prior to be beta distribution. Now have just specify both the prior and the posterior. The lift calculation is the deterministic process after we get the posterior.

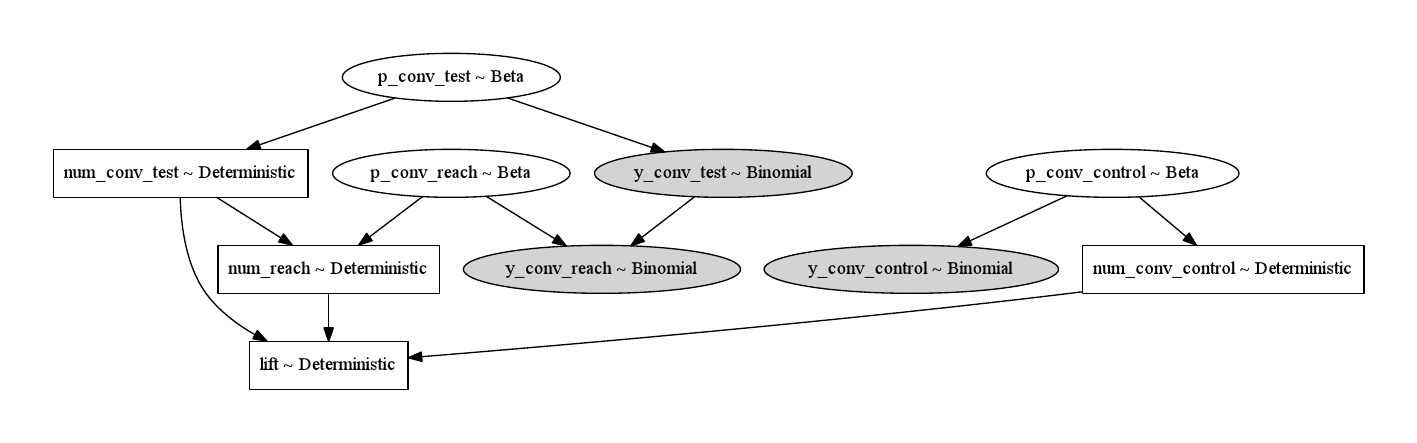

Figure 1. graphical diagram representing dependency among the variables. The random variables are in ellipses. The deterministic variables are in boxes. The shdaded ellipses represents likelihood.

# alpha and betas are the hyperpriors for our prior beta distribution. We don't actually care about this number in the end.

alpha_ = 2

beta_ = 2

with pm.Model() as model: # context management

#define priors which are the p (for probability)

p_conv_control = pm.Beta('p_conv_control', alpha=alpha_, beta = beta_)

p_conv_test = pm.Beta('p_conv_test', alpha=alpha_, beta = beta_)

p_reach = pm.Beta('p_conv_reach', alpha=alpha_, beta = beta_)

#define likelihood

# this is used to update the prior given the data (the observed)

#the fitting is a comparison between y_conv_control and the h_control and use the MCMC to match the two.

y_conv_control = pm.Binomial('y_conv_control', n = n_control, p = p_conv_control, observed = c_control)

y_conv_test = pm.Binomial('y_conv_test', n = n_test, p = p_conv_test, observed = c_test)

y_conv_reach = pm.Binomial('y_conv_reach', n = y_conv_test, p =p_reach, observed = c_reach)

#note here that size of n here in the conversion of reach group comes from the conversion in the test group, this is the hierarchical structure we talked about.

# derived

# This is the theoretical numbers that our model generates. Will use these numbers to calculate the lift according to our model

num_conv_control = pm.Deterministic("num_conv_control",p_conv_control*n_control) # number of people in the control group that convert according to our model

num_conv_test = pm.Deterministic("num_conv_test",p_conv_test*n_test) # number of people in the test group that convert according to our model

num_reach = pm.Deterministic('num_reach', p_reach*num_conv_test) # number of people who convert whom the ad is reached

scaling_factor = n_test/n_control

num_conv_control_scaled = (num_conv_control*scaling_factor)

baseline = num_conv_test - num_reach

Y = num_conv_control_scaled - baseline #number of conversion by those in the control who has a chance to see an ad but actually didn't see.

lift = pm.Deterministic("lift", (num_reach - Y)/(Y))

# inference

trace = pm.sample(5000, tune=2000, nuts_kwargs={'target_accept': .95})

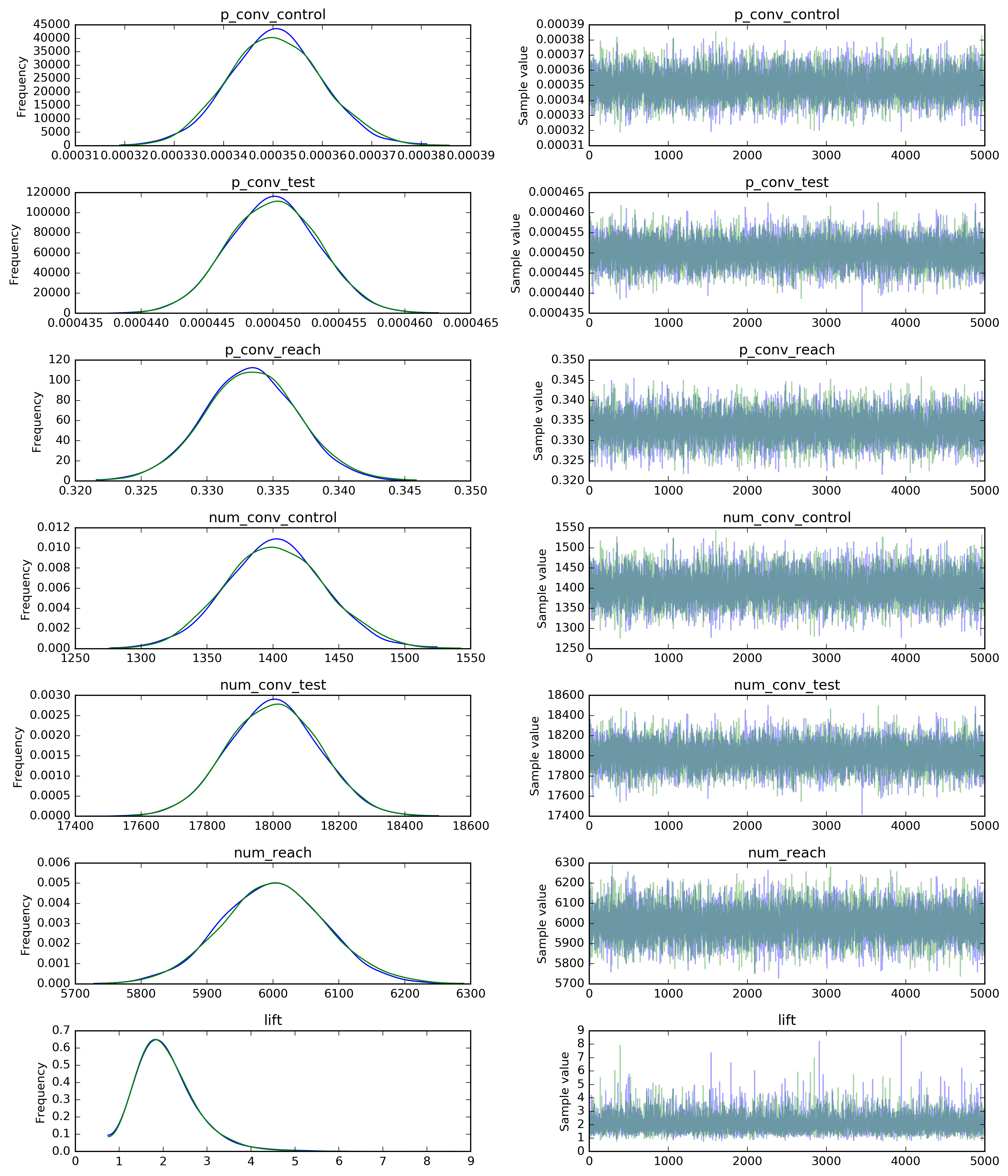

Figure 2. bayesian simulation of the probability and the lift result.

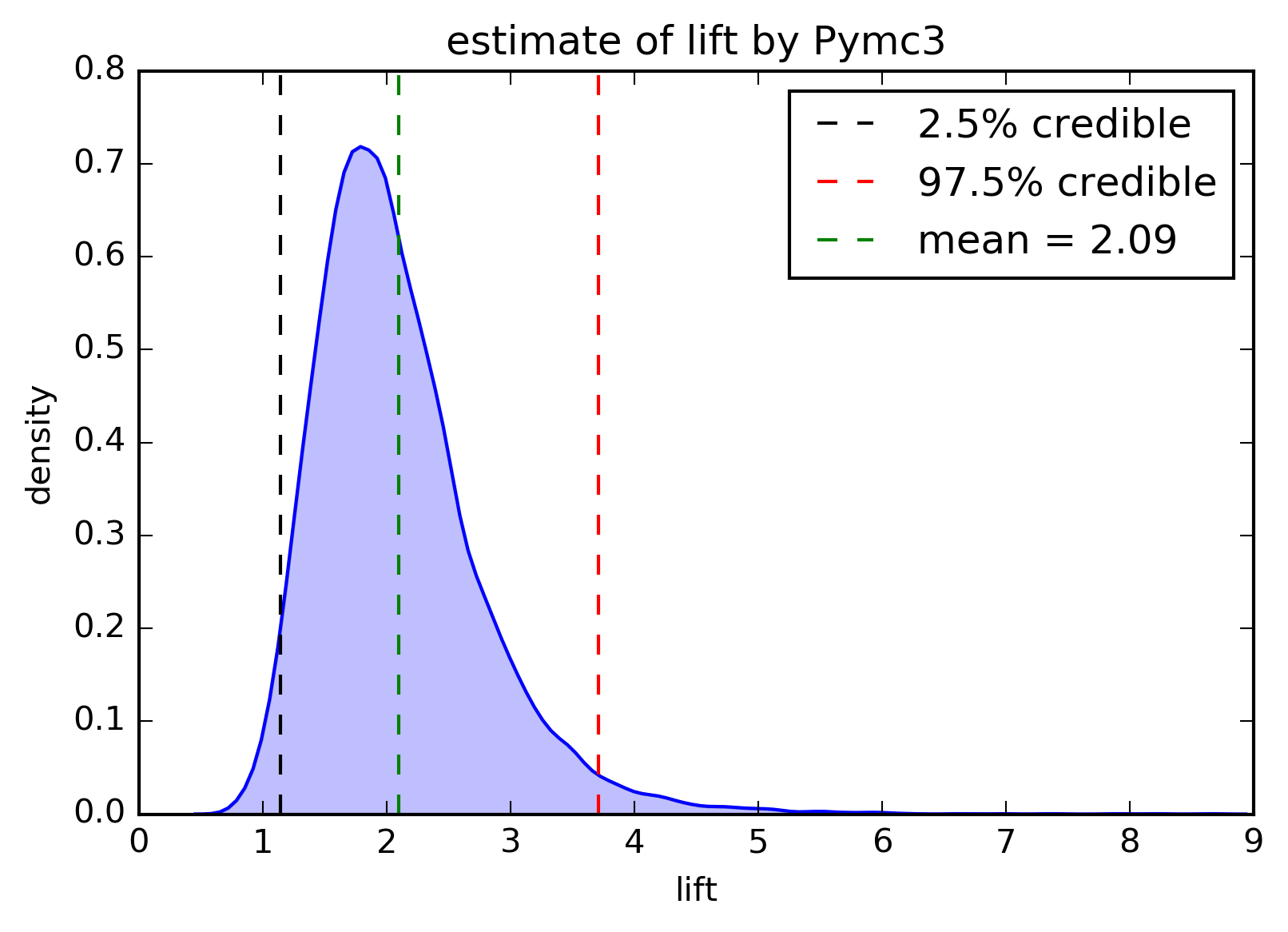

Figure 3. the lift result and the credible interval.

What does the result mean?

The p_conv_control gives us a probability that a random person will become a customer. The mean lift value is about 2, meaning seeing an ad doubles the probability that someone will subscribe compared to someone who has similar attributes but doesn’t see the ad. The result this high will make the marketers jump up and down. The realistic figure should be much less.

Appendix

1. What exactly is being measured in the experiment?

Earlier I said the lift is proportional impact of an ad on convertion given they see the ad (compared to not seeing the ad). The question is how long ago did they see an ad? Recall that the experiment has a set window of time that the data is collected. So more accurately, the lift is proportional short-term impact of an ad on conversion given they see an ad within a window period. The randomized control trial such as this may be suitable for short-term impact, but it may not be suitable for studying of a longer term impact of an ad as running a control group for a long window can be costly.

What is the interpretation when the same ad is shown to general population prior to the experiment? If the ad is out there , that’d mean that the the long-term effect of ads that were shown to both control and test groups prior to the experiment will be measured as baseline. This causes us to underestimate the impact of the ad.

2. What is Markov chain Monte carlo algorithm?

Before we talked about MCMC, let’s talk about a simpler way to perform a simulation-based approach to find the posterior distribution. One way to do the simulation is we perform a grid-sampling by defining an interval of parameters, and place a grid of points in the interval, draw a point in the grid to compute the likelihood and prior. Now if we have infinite points, we will arrive at the exact posterior distribution. But this method becomes unfeasible as the number of parameters increases because the shape of posterior distribution gets more and more complex, and the volume of posterior distribution becomes much narrower compared to the whole parameter space. This makes simple grid sampling unable to find the region in parameter space where posterior distribution is not zero.

From that intuition, this is where MCMC comes in.

We need a way to sampling points in high dimensional space such that we samples more points from the region that has greater probability (and not spend too much sampling in region where posterior is null). The sampling part here is the Monte-Carlo part.

The second part, Markov chain, describes a sequence of states and probabilities describing the transition among the states. The states are the parameters in the parameter space, so if we find the transition probabilities that is proportional to the likelihood, we will spend more simulations on the parameter space that is associated with higher posterior distribution.

There are many ways to find the transition probabilities that has such property. One way to do it is Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. Actually, the Pymc3 implements a newer method known as No-U-Turn sampler (NUTS). read here for more information.

So what is Metropolis-Hastings? This algorithm tries to guide us to spend time in region of parameter space proportional to the probability of posterior distribution.

- we choose an initial random point x_0 in parameter space.

- choose an arbitrary probability density Q (usually Gaussian distribution) as a jumping distribution.

3.1 generate a candidate for the next sample, by picking from the jumping distribution.

3.2 we can either accept the new point and move there, or we reject the new point and stays where we are. The acceptance is computed as the acceptance probability

| p(x_i+1 | x_i) = min(1,(likelihood of x_i+1/likelihood of x_i)) |

3.3 pick a random value V from a uniform distribution on the interval [0,1], if the acceptance probability calculated in 3.2 is greater than V, then we accept x_i+1, otherwise stay at x_i. We keep iterates from 2 till we have enough samples.

The idea behind this algorithm is to move through the parameter space and if the new point is a higher density region, we sometimes accept the move but not always. The acceptance probability being compared to a random value ensures that the algorithm will spend proportional time to points with higher attitude.

The reason for comparing the acceptance probability with the random value is that if we deterministically accept a point with higher density, the algorithm becomes a way of solving the posterior maximixation. But we do not want the maximization at all. What we want is to map the parameter space, and this algorithm provide a way to backtrack away from the high density region (so we can explore other regions as well).

2. Comment on the statistical significance

Notice that in the end, we gets a distribution representing probability density that the true lift is located, and from that, we can get the 95% credible interval. The 95% credible interval tells us that we have 95% credibility to believe that the true value of lift lies in the range. The range of the credible interval is usually similar to the frequentist confidence interval, except in small samples or large informative priors.

We don’t have p-value to report, but this is a good thing. I hear all the time that people misuse test of statistical significance, including professionals as well. They either believe that having statistical significance is the affirmation of their alternative hypothesis; or failing to have statistical significance means no effect; or large statistical significance means large effect size. None of these is correct. But still people do it all the time it’s almost unconscious. And if you report the p-value to them, they can’t help but thinking about these wrong interpretations of statistical significance.